Good evening and thank you so much for coming to this evening’s Curriculum Night. I know it’s another evening event in what is generally already a busy week for most of us. But I feel that it’s so central and important for us to cometogether, and the reason is because parenting and teaching are hard, they are challenging subjects, if you will, and for most of us they are not the subjects we were taught in our schools. Raising children is not for the faint of heart. And so we need all the help we can get!

Curriculum Nights are about that. They’re about partnering together as a band of parents and teachers; they are for learning together about education, so that we can grow in our parenting and teaching, so that we can spur one another on and get better together at the incredibly important work that we are engaged in. Curriculum Nights help us grow. (So come to our next one on “Charlotte Mason and the Science of Learning”!)

Our mission at Clapham School is to inspire students with an education founded on a Christian worldview, informed by the classical tradition, and approached with diligence and joy. And that final phrase “approached with diligence and joy” is our theme for growing as a community this year, “an education approached with diligence and joy.” It’s a paradoxical phrase. I mean, isn’t diligence by definition painful, challenging, grievous and tedious? Anything but pleasant?

As the author of the NT book of Hebrews says of discipline rather than diligence: “For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant…” (Heb 12:11a ESV). And on the other hand, aren’t joyful things by definition easy, light, exciting and carefree? No, says our mission, joyful discovery is a paradox of passion and pain, challenge and hard-won victory, deliberate practice and incremental gains, just as all the great teachers, musicians, athletes, and experts have proven down through the years. Diligence and joy go hand in hand. It may be really tricky to maintain both, but when we do they become the magic sauce that makes incredible growth possible.

This last June I witnessed an example of this in my own daughter Alethea. She had just turned 1 year old, and had just been walking for a few weeks, and I took here outside to a park right behind our place. And around this park there’s a slope of grass circling it that’s between 20 and 30 feet elevation drop. So of course, I carry her down to the field so that she can run around down there. But instead what she proceeds to do is head right back up the slope. Now she’s just learned to walk, mind you, and her steps are still unsteady. But with a big grin on her face and a determined look, she starts heading up part of the slope, and then back down again, taking a fall here or there. I’m watching her closely, don’t think I’m neglectful parent or anything.

But basically, for the next twenty minutes with joy radiating from her face, she sets for herself the challenge of walking up and down hill. Level grass is too easy for her. In fact, some of the times as she was coming down the slope she was practically cackling to herself with exuberance for her accomplishment of this extra challenge. Now obviously not every child is like that for everything, but I think it illustrates the point that as human beings we’re most alive, joyful, and on fire, when we are pursuing some worthy goal for growth with all of our might.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi proved this in a study conducted in the 90s in which subjects would subjectively rate their mood at random times throughout the day. As Cal Newport describes it in his book Deep Work:

“The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile…. Csikszentmihalyi calls this mental state flow (a term he popularized with a 1990 book of the same title). At the time, this finding pushed back against conventional wisdom. Most people assumed (and still do) that relaxation makes them happy. We want to work less and spend more time in the hammock.” (84)

The opposite is actually true; people rated their work time much higher than their leisure time, in spite of thinking that they enjoyed their leisure time more. As human beings we were made to be most joyful when diligently devoted to a worthy pursuit, when engaged in deep work, or deliberate practice.

Well, if you’ve been around Clapham School for a while, you probably also know that this approach marked by diligence and joy is one of our ways of referring to the inspiring thought of that brilliant Christian educator, Charlotte Mason. Charlotte Mason lived from 1842-1923, and though she never had the opportunity to have children herself, she inspired a national movement of parents, called the PNEU or Parents National Education Union. At the helm of this organization, Charlotte Mason pioneered a way to bring a classical liberal arts education into the modern world.

She fought against some of the pernicious tendencies of early progressive education, like the idea that some students can’t learn and don’t deserve to read the great books, or that Latin should be cut out of the curriculum, because it’s not practical, or the use of dessicated textbooks dried out of the lifeblood of flavor or interest. Instead she devised a philosophy of education founded on the Christian idea that children are persons, made in the image of God, and that every aspect of how we educate them as parents and teachers should be radically transformed through that principle.

So much of what goes wrong in education stems from a failure to fully recognize the personhood of each and every individual child, and give them the respect, honor, and challenge that bring out their full humanity, give them joy, and spur them on to growth.

And in this way Charlotte Mason anticipated many of the findings of modern research. One of Charlotte Mason’s goals for the parents education union, was to give Christian parents the support they needed through both going back to the best philosophy, from Plato and Aristotle to Bacon and Coleridge, but also to incorporate the findings of modern research from within a Christian worldview. As she said in a draft for the parents union,

“[Parents], who must do the vital part of the world’s work, compare at a disadvantage with all other skilled workers, whether of hand or brain. There is a literature of its own for almost every craft and profession; while you may count on the fingers of one hand the scientific works on early training plain and practical enough to be of use to parents.”

– Cholmondley’s The Story of Charlotte Mason, 23

That again is one of the things we’re trying to do through our three Curriculum Nights throughout the year, and through our blog on the website. We don’t want to just be another private school; instead, in keeping with our namesake of the Clapham Saints, we want to be a community of likeminded parents, raising our children together alongside a team of educators, teachers, administrators, coaches and mentors.

So with the rest of our time as a big group, I’d like to share with you about a modern research finding that Charlotte Mason anticipated. And that is Carol Dweck’s idea of a growth mindset vs. a fixed mindset. Carol Dweck is a world-renowned Stanford University psychologist, who discovered a simple but profound idea: that what people believe about themselves and about their traits has an enormous impact on whether or not they develop and succeed. As Christians we might not be so surprised to find that our beliefs deeply impact our lives, but this has been ground-breaking and made a lot of waves among educators, athletes, musicians and in business. The basic idea goes like this: people with a fixed mindset believe, more or less, that their abilities in a particular area are fixed, they can’t change them. Either they’re smart or they’re dumb, either they’re talented or they’re not. People with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believe that their abilities can be developed; they can grow, they may not be able to become the best in the world, but they should still work hard and try.

What Carol Dweck also found in her studies is that the fixed and the growth mindset are catching; they’re communicated to children in the subtle messages that parents and teachers and coaches send. Her studies found that the wrong type of praise can backfire and have the effect of inculcating a fixed mindset and actually demotivating children. One of her students at Columbia University reflected on his own experience:

“I remember often being praised for my intelligence rather than my efforts, and slowly but surely I developed an aversion to difficult challenges. Most surprisingly, this extended beyond academic and even athletic challenges to emotional challenges. This was my greatest learning disability—this tendency to see performance as a reflection of character and, if I could not accomplish something right away, to avoid that task or treat it with contempt.”

– Dweck p179

This is how it works. A simple praise statement, like “You learned that so quickly! You’re so smart!” or “You’re so brilliant, you got an A without even studying!” gets interpreted in a fixed mindset as “If I don’t learn something quickly, I’m not smart” and “I’d better quit studying or they won’t think I’m brilliant.”

Now at this point you might be skeptical about whether normal kids really interpret our praise that way. But Dweck’s findings aren’t based on some flimsy anecdotal evidence; as she says in her book, “After seven experiments with hundreds of children, we had some of the clearest findings I’ve ever seen: Praising children’s intelligence harms their motivation and it harms their performance.” People with a fixed mindset are incredibly anxious about failure, because they think, if I fail at something, that might be a sign that I’m dumb or untalented. And so often they go to great lengths to blame anyone and anything other than believe that. She tells the story of this famous tennis player, who viewed himself as a natural and practiced less, because he felt he didn’t need to; ultimately, as he descended further and further in the rankings, he was blaming the wind, shouting at the people bringing him water, lashing out at everyone around him, because he was the best, pure and simple, and if he wasn’t winning it had to be someone else’s fault. In the same way a student with a fixed mindset does fine when everything is going well for him or her, apart from looking down on others, but when the slightest challenge or difficulty comes their way, they lash out or shut down. Praise and reassurances that they are smart just backfire.

So if praising children for being smart or talented tends to inspire a fixed mindset, how should we praise our children? Well, some of the skepticism that’s out there about the growth mindset has its basis in a lot of people misunderstanding what Carol Dweck says here. For example, many have jumped on the bandwagon of growth mindset language and thought that meant they should praise their children for effort rather than success. But this is a major simplification. What Dweck says is that we should praise them for following the right process, which includes effort, but also trying new strategies when what they’re doing isn’t working and getting help or input from others. In the book she says,

“More than once, parents have said to me, ‘I praise my child’s effort but it’s not working.’ I immediately ask, ‘Was your child actually trying hard?’ ‘Well, not really,’ comes the sheepish reply. We should never think that praising a process that is not there will bring good results.” (215)

So our first take away from tonight is, Don’t praise for your child for fixed traits, as if they weren’t a growing person but a finished product. It tends to make them more worried and anxious and less motivated to persevere through challenges where they might initially fail.

But honestly, failure’s hard; it’s hard to deal with our children failing in some way. We want to protect them, and to a certain extent we’ve all been influenced by the self-esteem movement that says we should praise our children no matter what and make sure they don’t ever experience failure. Believe it or not, Charlotte Mason dealt wCHARLOTTE MASON AND THE GROWTH MINDSET with this same feeling from parents in her own day. She quotes from an Indian scientist who conducted an experiment on a plant:

“A plant carefully protected under glass from outside shocks looks sleek and flourishing but its higher nervous function is then found to be atrophied. But when a succession of “blows” (electric shocks) “is rained on this effete and bloated specimen, the shocks themselves create nervous channels and arouse anew the deteriorated nature. Is it not the shocks of adversity and not cotton wool protection that evolve true manhood?’” (Vol. 6 Toward a Philosophy of Education)

I find this passage inspiring and convicting. Sometimes we have to let our kids struggle and fail; face adversity and challenge; it’s part of a long-term process of growth.

In a section on parenting, Carol Dweck also addresses the issue of how we as parents should help our children deal with failure. I just have to share with you this real-life story she tells in the book.

“Messages About Failure” story from Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, pp. 183-185:

“Nine-year-old Elizabeth was on her way to her first gymnastics meet. Lanky, flexible, and energetic, she was just right for gymnastics, and she loved it. Of course, she was a little bit nervous about competing, but she was good at gymnastics and felt confident of doing well. She had even thought about the perfect place in her room to hang the ribbon she would win.

“In the first event, the floor exercises, Elizabeth went first. AlthoCHARLOTTE MASON AND THE GROWTH MINDSETugh she did a nice job, the scoring changed after the first few girls and she lost. Elizabeth also did well in the other events, but not well enough to win. By the end of the evening, she had received no ribbons and was devastated.

“What would you do if you were Elizabeth’s parents?1. Tell Elizabeth you thought she was the best.

2. Tell her she was robbed of a ribbon that was rightfully hers.

3. Reassure her that gymnastics is not that important.

4. Tell her she has the ability and will surely win next time.

5. Tell her she didn’t deserve to win.“There is a strong message in our society about how to boost children’s self-esteem, and a main part of that message is: Protect them from failure! While this may help with the immediate problem of a child’s disappointment, it can be harmful in the long run. Why?

“Let’s look at the five possible reactions from a mindset point of view—and listen to the messages:“The first (you thought she was the best) is basically insincere. She was not the best—you know it, and she does, too. This offers her no recipe for how to recover or how to improve.

“The second (she was robbed) places blame on others, when in fact the problem was mostly with her performance, not the judges. Do you want her to grow up blaming others for her deficiencies?

“The third (reassure her that gymnastics doesn’t really matter) teaches her to devalue something if she doesn’t do well in it right away. Is this really the message you want to send?

“The fourth (she has the ability) may be the most dangerous message of all. Does ability automatically take you where you want to go? If Elizabeth didn’t win this meet, why should she win the next one?

“The last option (tell her she didn’t deserve to win) seems hardhearted under the circumstances. And of course you wouldn’t say it quite that way. But that’s pretty much what her growth-minded father told her.

“Here’s what he actually said: ‘Elizabeth, I know how you feel. It’s so disappointing to have your hopes up and to perform your best but not to win. But you know, you haven’t really earned it yet. There were many girls there who’ve been in gymnastics longer than you and who’ve worked a lot harder than you. If this is something you really want, then it’s something you’ll really have to work for.’

“He also let Elizabeth know that if she wanted to do gymnastics purely for fun, that was just fine. But if she wanted to excel in the competitions, more was required.

“Elizabeth took this to heart, spending much more time repeating and perfecting her routines, especially the ones she was weakest in. At the next meet, there were eighty girls from all over the region. Elizabeth won five ribbons for the individual events and was the overall champion of the competition, hauling home a giant trophy. By now, her room is so covered with awards, you can hardly see the walls.

“In essence, her father not only told her the truth, but also taught her how to learn from her failures and do what it takes to succeed in the future. He sympathized deeply with her disappointment, but he did not give her a phony boost that would only lead to further disappointment.”

Now there are so many things that could be said about this example, but I want to start by saying that this idea of a growth minded response to challenge, struggle, and even failure (a word we hate to even use) is deeply counter-cultural. I also believe that, as Christians who are committed to embracing truth and reality as it stands, its something we absolutely need to move in the direction of, ultimately because this little finding of modern psychology happens to give us just a glimmer of the gospel. We are all sinners, we are all foolish, we are all failures, but because of the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ we are all loved and accepted, and our identity is in Him, not in what we do or how we perform, and because of that we can grow in joyfully obeying God by the power of His Spirit. Christians, of all people, should be the most growth minded.

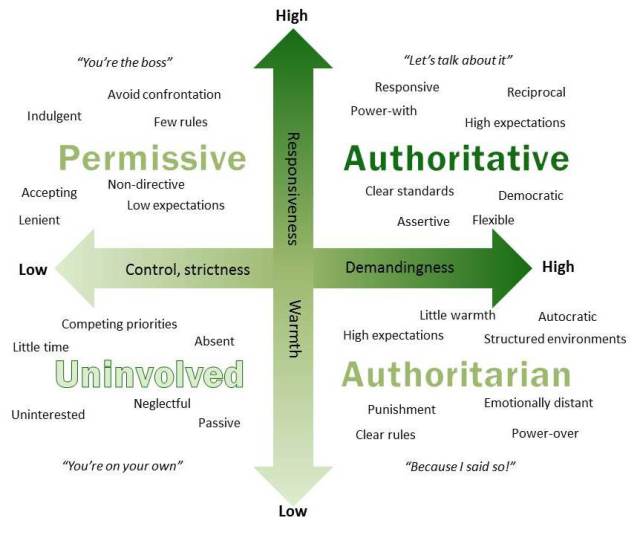

This also happens to be the paradigm called authoritative parenting that Angela Duckworth in Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance said makes gritty children, who are able to endure challenges and get stronger because of them. Each of us is probably more inclined toward warmth or strictness, being nurturing or expressing high standards, but the secret sauce of life is apparently to be both exactly at the same moment. It reminds me of how Paul in Romans talks about both the kindness and the sternness of God (cf. 11:22).

Well, I want to conclude by taking a moment to apply this to us as a school, as an organization. Here at Clapham we are about growth, and that means striving to improve at everything we do, so that we can help our students grow more and more in all areas of their personhood and humanity. And as I’ve mentioned truthful and honest feedback, along with the belief that we can grow and make progress, are absolutely critical to that. And that’s one of reasons why we’ve gone through the accreditation process with ISACS, the Independent Schools Association of the Central States. This year is the first year in our second time through the 7 year cycle of reaccreditation, and the main agenda item for this year is the Community Survey, which is going to give us important data as we conduct a full self-study next year. This community survey is so critical, because we really want the best data we can get about your perception of every aspect of our school, and the best way to do that is to get everyone participating fully.

I just want you to know too that even tonight for this Curriculum Night, we’ve made a few strategic changes, based on the feedback we got from you all last year from that informal survey: the coffee, the handouts, providing an opportunity to hear from Laura about Art and Julie about Music. We got some great feedback and ideas from you all last Fall; thank you for that! We want you to know that we really value your feedback and we want to improve. We’re not crushed by negative feedback; we don’t want to have a fixed mindset as an organization, thinking that Clapham School’s already perfect as it stands, but we’re motivated and working hard with all the resources at our disposal to improve in every way we can. So as you are able, help us improve. A pastor I know used to say that if you have a vision for how something could be better, maybe that’s the Lord nudging you to serve; volunteer with us. Let’s together make this the best school we can for God’s glory and the good of our children. We’ll be sending out little mini-surveys as well after events like these, throughout the year. It takes a village to raise kids and we’re doing this together as a community. So let’s grow together.

Well, that concludes my address on Charlotte Mason and the Growth Mindset. I’d encourage you to take a moment, think about it. What struck you, what landed for you, what are you going to do differently as a parent, as a teacher, because of this? I highly recommend Carol Dweck’s book Mindset as well as Angela Duckworth’s Grit, but even more Charlotte Mason’s volumes are just jam-packed with practical insight from a Christian worldview. Ashley and I are reading aloud Charlotte Mason’s Home Education right now, and it’s very inspiring and convicting all at the same time. So I would encourage you to invest in yourselves as parents and teachers; I think you’ll find it’s really worth it.

Fall Curriculum Night Address 2018